Basic concepts

The way Wireframe works is based on the MVC (Model View Controller) pattern. We say "based" because, quite frankly, Wireframe isn't a strict MVC implementation and that has never been the goal of this project. You could say that Wireframe is MVC-inspired, or perhaps MVCish.

If MVC is a new thing for you, you can find a lot of quality content from all over the web. It's one of the most influential software design patterns out there, after all. Anyway, quite likely the most important thing to understand about MVC is that it emphasizes this idea known as separation of concerns:

- Model represents data and business logic.

- View is the visible representation of said data, or the UI.

- Controller acts as the interface between end-user and your site.

What this means in theory is that you should be able to work independently on each of these layers. While things are not always quite that simple, this is indeed one of the core concepts behind the Wireframe framework: it should be possible to rewrite entire front-end of a site without touching any backend code, and vice versa.

The hardest part was to hit upon good names for the different architectural components.

— Trygve M. H. Reenskaug

MVC !== MVC

The MVC pattern was originally devised as a way to manage desktop software, and the pattern was first implemented on the Smalltalk programming language, which in turn is nearly fifty years old by now. Since the introduction of the MVC pattern in 1978 at Xerox PARC it has evolved – and been adapted – numerous times for many different purposes.

Keeping the long and colourful history of MVC in mind, it's not particularly surprising that there are many, many variations of it floating around. Wireframe is no exception: even if you've already developed applications using the MVC pattern, the way we're using MVC in the context of Wireframe likely isn't exactly what you're used to.

One particularly notable difference is that there's no "Model" component in Wireframe.

... like, seriously. That's not a joke.

If you're wondering why on earth would we drop a whole letter from the MVC — that's, like, one third of the whole shebang! — the reasoning behind this particular design decision is actually pretty simple: in the context of a ProcessWire site, ProcessWire itself is the model. In other words there's no need for a model layer in Wireframe.

That "fat model, thin controller" mantra you might've heard of? Doable, but unless you're really adamant about staying true to all the MVC best practices you've been taught, our advice is to take a deep breath — and let it go. In Wireframe, Controllers will usually host the vast majority of your business logic.

The core components of the Wireframe framework from the bootstrap file to partials – and everything in-between

Below you'll find a breakdown of the core concepts (and components) one will likely run into while working with Wireframe. Don't worry if you don't grasp everything on the first read; we're going to dig deeper into the specifics of each component later in the docs.

Wireframe bootstrap file

The Wireframe bootstrap file is a single file in your /site/templates/ directory, typically named wireframe.php. This file is set as the value of the Alternate Template File setting for templates you want to utilize Wireframe for, and it is responsible for bootstrapping the Wireframe framework.

Even though the bootstrap file is just that – file, and not an object – it could be seen as a kind of a front controller: each time ProcessWire renders a page, this file gets executed, which makes it a sensible place to add any code that applies to all of your templates.

This is where you typically would provide Wireframe with settings, such as a site name, language, etc. For an example of a bootstrap file, see the About page, and for a default (bare-bones) Wireframe bootstrap file check the Wireframe module directory.

You can have more than one bootstrap file if you need to. This could make sense if you have some major differences between your templates, but note that it would obviously diminish the benefits you gain from using a common entry point for all requests.

Model

Wireframe is MVC-ish, and one reason for the "-ish" suffix is that there's no literal Model component in the entire framework.

Wireframe treats ProcessWire as the model: you can access ProcessWire's API both from your Controllers and Views, and most tasks commonly associated with the Model – such as fetching data from the database, aggregating content items, or creating new items – can be easily achieved with some simple API calls.

View

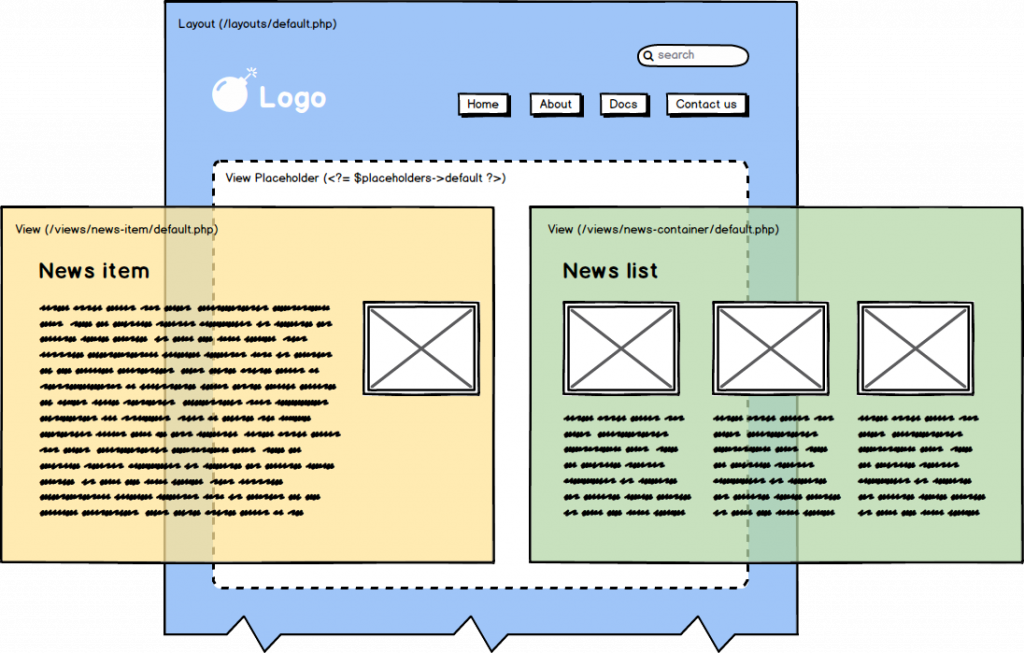

The View component is essentially the current rendering context. You can pass params from Controller to View using the $view API variable ($this->view, since Controllers are classes derived from the Wire object), and those params will become locally scoped variables in your layouts, views, and partials (<?= $this->some_var ?>).

Note that you can also access the $view API var from within layouts and views. This is useful as it makes it possible to pass data from a view file to the layout. Keep in mind, though, that due to the rendering order passing data from a layout to a view file is not currently possible.

Controllers

Controllers are optional template-specific classes. Their main responsibilities include processing user input, fetching data from the Model (ProcessWire), formatting said data as needed, and finally passing it to the View.

In Wireframe Controllers should contain business logic related to the template – or, at least, any business logic that doesn't clearly belong to a separate module or class. One of the key concepts of MVC is separation of concerns, and one of the first steps towards that is not mixing business logic with markup generation.

Note that Controllers are indeed optional: if a Page can be rendered without complex business rules (meaning that you only need some basic control structures, loops, and echo/print statements), it is perfectly fine to leave Controllers out of the equation and request data directly from ProcessWire's API in layouts or views.

(When a Page is rendered, Wireframe checks if it can find and instantiate a Controller class. If it can't, it'll continue rendering the Page without one.)

Layouts

A layout is a wrapper (container) for page content. Most sites will likely only need one layout, or perhaps two – although this of course depends a lot on the site itself. Page-specific content is typically rendered using a view file and then injected into the layout using what we call View Placeholders.

Layouts are recommended, but technically optional. If you find that many of your pages include an identical (or almost identical) basic structure, such as a common header and footer, you can always include partial files for these common parts on each view – but that's also where layouts shine.

By moving those shared parts of the page markup into a layout file you avoid having to add include clauses all over your views.

View files

Not to be confused with the View class – which is the component that encompasses both layouts and view files – view files are implementations of individual views for a page. In other words they are used to render actual page content.

Each template may have one or more view: often you will only need one to render page content, but you can add additional views for rendering page content in different ways, or in different contexts – or just to render different parts of the same page in separate locations in one layout.

For an example a news-list template could have a "default" view for rendering a HTML markup for a news list, an "rss" view for rendering the child pages (items) as a machine-readable feed, a "json" view for some sort of custom JSON API, and so on. In addition to varying content, for each view you can specify different content type as well.

By default views are PHP files, which means that you could include business logic within them. Regardless, it is strongly recommended that you keep your view files as "dumb" as possible. Typical view level tasks include outputting content, and simple loops and other basic control structures.

View Placeholders

View Placeholders are the preferred way to inject the rendered page content – or any markup and/or variables produced by Controllers for that matter – into a Layout. You could say that View Placeholders create "slots" in layouts that you can then fill with applicable content.

When you want to embed page content (from view files) into your layout file – the "frames" of your site, containing all the elements common to all pages – you can start by echoing out the placeholder slot in a layout file:

<main>

<?= $placeholders->default ?>

</main>

Now, there are two ways to actually fill a placeholder slot with content. One of them is "pushing" content into the slot from a Controller class:

<?php

namespace \Wireframe\Controller;

class BasicPageController extends Controller {

public function render() {

$this->view->placeholders->default = $page->body;

}

}

While that's handy for some use cases, probably the most typical case is based on the view files themselves: if you echo $placeholder->default, Wireframe will automatically look for a view file called "default" (/views/[template]/default.php) run-time, and if it finds one, it renders the page with that view file and fills the slot with resulting content.

Partials

Partials are smaller pieces of markup (usually specific parts or elements of the site) you can include within view or layout files. Partials can come in handy any time you want to split a view file into smaller, more manageable chunks – but they are especially useful when it comes to defining reusable UI components.

Partials are embedded using PHP's native include or require commands:

<?php include 'partials/menu/top.php'; ?>

Wireframe also provides an alternative, object oriented way to access partials:

<?php include $partials->menu->top; ?>

Components

Components are much like partials, except that they typically consist of two separate files: a class that extends the \Wireframe\Component base class, and an optional component view file – of which there may be none, exactly one, or more than one, depending entirely on the needs of that particular component.

While partials are great for relatively static snippets of markup, components have the innate capability to perform different types of operations – calculations based on their arguments, transformations of data, API requests, etc. – without unnecessarily mixing business logic with markup generation.